Beats for Humanity: Drumming with Microtime [Part 1]

Drum machines and sequenced percussion are incredibly common elements in many styles of modern music. When drum machines first hit the market, some human drummers (which we’ll just refer to as “drummers”) felt a little threatened. After all, drum machines possess a lot of desirable qualities: they keep perfect time, they’re never late to band practice, and they won’t ever destroy a hotel room in a drunken rampage. Seems like a pretty sweet deal!

However, the rigidity of literal perfect time and the need to program and sequence drum parts beforehand doesn’t necessarily work for all styles of music. A living, breathing drummer can much more readily adapt to the ebb and flow of live music, both in terms of dynamics and feel. That’s why there are still drummers today!

But some producers figured out how to sequence the organic feel of live drummers with drum machines by nudging some of the programmed hits ever so slightly off of the rhythmic grid. Oddly enough, this has led to a trend of drummers that seek to emulate the off-kilter feel of “humanized” drum machines. Things have come full circle!

Dilla Beats

The producer J Dilla was arguably the biggest influence on humanized sequenced beats. Using an Akai MPC3000 (pictured right), Dilla’s production style was a catalyst for the trend of adding some tasteful imperfection to drum grooves and backing tracks. One of the major draws to drum machines is their ability to quantize a performance, or snap it to a rhythmic grid so hits are mathematically even. Quantization allows even the loosest performances to sound perfect. Dilla basically said “Nah” to the idea of quantizing grooves and allowed certain elements of drum grooves, particularly the placement of the bass drum and hihats, to bend around the beats a bit. He was a master of microtime, or the spaces between each beat, and had a seemingly instinctual understanding of how to use it to his advantage.

Some drummers that have perfected the nuanced use of microtime include Chris Dave, Questlove, Perrin Moss (Hiatus Kaiyote), Ian Chang, and Zach Danziger (among many others).

But playing real drums with that kind of purposeful imperfection actually requires a very high level of control and timekeeping abilities. In order to begin moving things off of the rhythmic grid, we first need to know what the rhythmic grid is and how to play on it. Long story short, rhythms are built upon a consistent underlying pulse, known as the beat. The beat can be divided into smaller parts, known as subdivisions. These subdivisions create a grid that we can fix rhythms to.

In this installment (the first of three), we’re going to explore 8th note, triplet, and 16th note rhythmic grids, and some ways to simulate getting off the rhythmic grid. Check out this blog post for a deeper dive into the rhythmic grid!

8th Note Grid

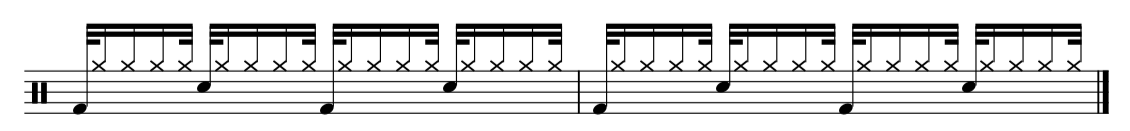

8th notes are achieved by splitting each beat into 2 equal parts. In most hiphop and rock grooves, drummers play steady 8th notes on the hihats. As a starting point, the kick typically plays on beats 1 and 3, and the snare on beats 2 and 4 (the backbeats). Written out, a basic groove looks like this:

A simple groove like this one is a great starting point for beginning to shift around the rhythmic grid a bit. Instead of playing the hihats and kick or hihats and snare at the exact same time, we can play flams between the two voices to slightly blur the underlying beats. By playing the hihats a slight fraction of a beat before or after the kick and snare, we can achieve a form of that sought-after purposeful imperfection.

These first two videos demonstrate playing the hihats just before the beats.

These next two videos demonstrate playing the hihats just after the beats.

Triplet Grid

Splitting each beat into 3 equal parts gives us 8th note triplets. Triplets are the foundation of the swing feel, which is characteristic of the blues, jazz music, and shuffle grooves.

Dilla was able to make hiphop grooves swing in a unique way by sometimes blending different rhythmic grids together. If we played a shuffle pattern on the hihats (the first and last triplets of each beat), but an 8th note pattern on the kick, the resulting groove feels pretty wobbly since it’s built upon two rhythmic grids that don’t cleanly align with one another. It almost feels as though the hihats should land on the ‘&’ of each beat, aligning with the kick, but they happen just a smidge late. The groove straddles the line between regular 8th notes and 8th note triplets. Although this groove technically makes use of 2 rhythmic grids simultaneously (which seems like the opposite of the objective of getting off the grid), it still creates the unsteady feel we want to utilize.

Dividing 8th note triplets into 2 parts a piece puts us into the realm of 16th note triplets, which entails splitting beats into 6 equal parts. Further dividing beats allows for more detailed positioning of hihat hits and kicks. This next groove uses steady 8th notes on the hihats, but they’re offset behind the beats by a single 16th triplet. In this case, the hihats never actually line up with the kick or snare. Although this groove is pretty calculated, it certainly feels somewhat rhythmically ambiguous.

16th Note Grid

Splitting beats into 4 equal parts (or each 8th note into 2 smaller parts) results in 16th notes. 16th notes are incredibly common and work cleanly in conjunction with 8th notes.

Even a sparse pattern on the hihats can make a groove limp (in a good way) using crafty 16th note positioning. For example, playing the hihats on only the ‘a’ of each beat (the last 16th note of each beat) while playing a straight-ahead pattern between the kick and snare yields a groove that feels a little clumsy.

We can also play steady 16th notes on the hihats, but nudge them ever so slightly off of the beat (by a 32nd note, or half of a 16th note, to be precise). This combination is particularly difficult to play since it really fights against any developed muscle memory. The hihats feel like they should align with the kick and snare on each beat. Keeping them offset by such a small fraction of a beat is much easier said than done!

Those are a few ways to dip your toes into the use of microtime using common rhythmic grids. In the next installment, we’ll explore how we can use less common rhythmic grids, particularly quintuplets and septuplets, to create grooves with an even more viscous feel to them. With enough practice, you’ll develop a strong internal sense of time and the ability to phrase rhythms ever so slightly off of beats without causing the groove to suffer.